$ USD

-

$ USD

-

€ EUR

-

£ GBP

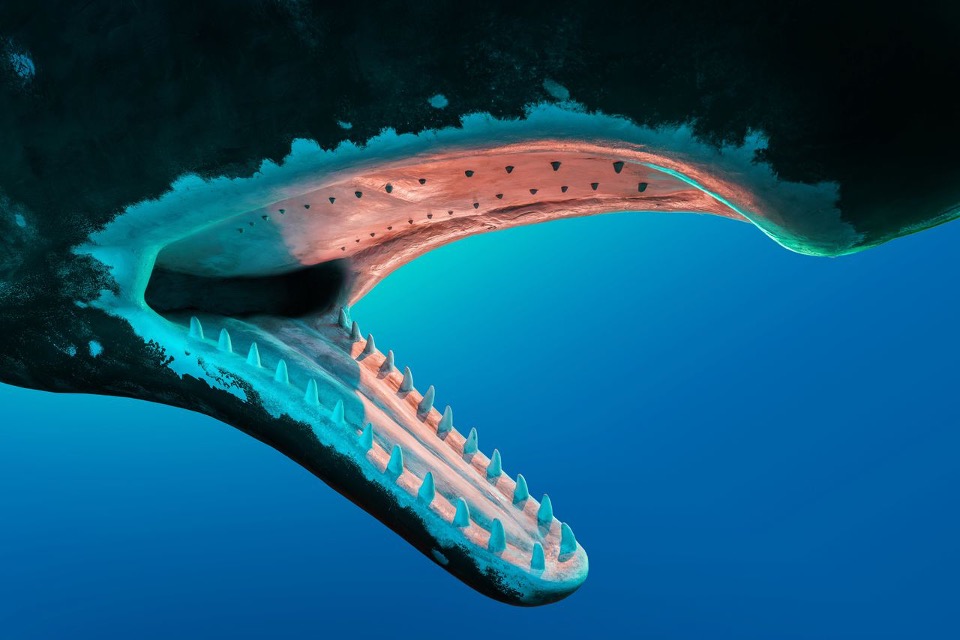

A sperm whale on the beach at Vlieland, in 2021. A humpback whale near Burgh-Haamstede in Zeeland, last summer. Whale strandings occur regularly in the Netherlands. But over the years, all kinds of long-extinct marine mammals have also washed ashore. Fossils of primeval whales, for example, which ruled the seas in the Eocene epoch, around 50 million years ago. One of the most renowned collectors of marine mammal fossils is fisherman Klaas Post, who was affiliated with the Natural History Museum Rotterdam as an honorary curator for over twenty years and also participated in several international expeditions to learn more about whale evolution.

Klaas Post and Noud Peters: The Fossil Marine Mammals of the Netherlands – From Miniature Seals to Giant Sperm Whales. Publisher: GBU Printmedia, 112 pages. €19.50. Available to order via pleistocenemammals.com.

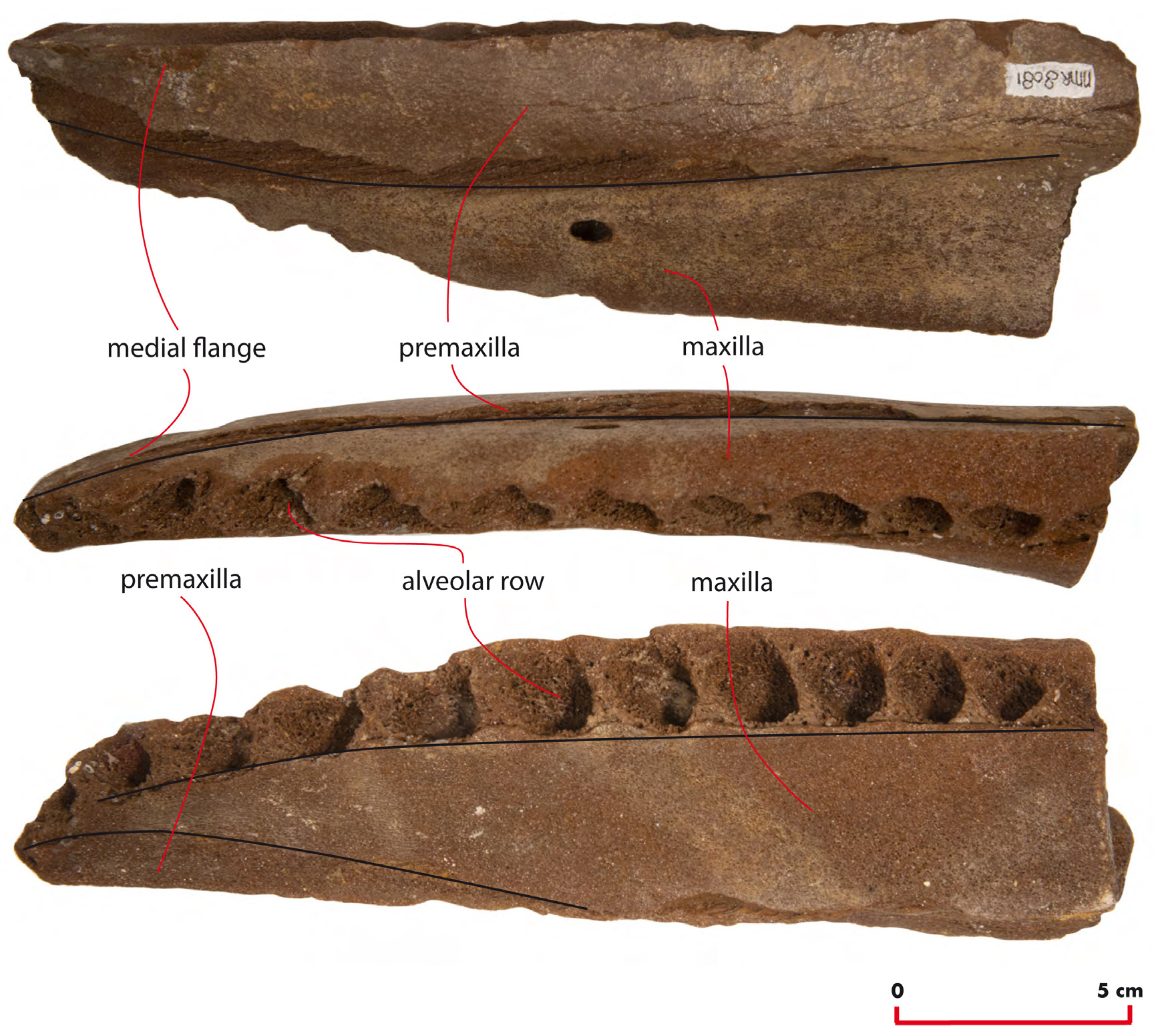

In The Fossil Marine Mammals of the Netherlands – From Miniature Seals to Giant Sperm Whales, Post joins forces with Noud Peters, fellow collector and biologist. Together, they bring that early underwater world to life with countless fossil photos and background stories. As you read, you travel back in time, for example to the moment when the first cetaceans left land for the sea, and you learn about the evolution of whales and belugas, among others.

Peters and Post’s museum background is clearly evident in their educational texts, which not only discuss the different mammal families, but also delve deeper into topics such as skull structure, echolocation, and the hearing of marine mammals.

Sometimes the density of information is very high, and the enumeration of all geological eras and scientific names begins to make the reader’s head spin, making the text seem somewhat like a textbook. Fortunately, there are also many vivid asides—for example, about the impressive Steller’s sea cow that was discovered in the 18th century “in the cold waters of the Bering Sea” and measured no less than 8 meters in length. “The meat from one individual could keep 33 sailors alive for a month,” write Post and Peters. This probably led to its rapid extinction. “In 1768, only 27 years after its discovery, the last specimen of this species was killed.” Bones of sea cows are also easy to recognize, they write – not only because they have an unusual shape, but also because they are very heavy.

“It is believed that this is an energy-saving adaptation that allows them to graze quietly close to the bottom. The heavy bones serve the same function as the weight belt a diver wears to do a job underwater.” The many illustrations are also worth seeing, such as the painting of the Vischpoort in Elburg, which until 1838 incorporated a cervical vertebra from a gray whale.

The final chapter provides an overview of marine mammals in Dutch museums, so that after reading, you can go out and see them for yourself: spotting a sperm whale or a seal has never been so easy.